By Nambi E. Kelley

Based on the novel by Richard Wright

Directed by Seret Scott

Bigger Thomas dares to want more out of life. Things start looking up when he lands a plum job with the well-to-do Dalton family, but their daughter Mary proves to be as dangerous as she is alluring. A fateful decision sends Bigger down a violent and inescapable path. Misrepresented and underestimated by everyone around him, Bigger has no one to turn to except himself. Using W.E.B. DuBois' theory of double consciousness as a guiding principle, this fresh 90-minute adaptation of Native Son focuses on the landscape inside the mind of Bigger Thomas, bringing the power of Richard Wright’s novel to life for a whole new generation. MTC is proud to bring Ms. Kelley’s heart-stopping, urgent and expressionistic adaptation of Wright’s groundbreaking novel to the West Coast, following its sold-out World Premiere at Chicago’s Court Theatre in 2014.

Nambi E. Kelley was a finalist for the Francesca Primus Award for her work on Native Son, and is currently the 2015-2017 playwright in residence at The National Black Theatre in NYC. Ms. Kelley will be joining MTC’s artistic team and the play’s originating director Seret Scott for the MTC production.

★★★★★ Racism reaches boiling point in MTC’s ‘Native Son’

Marin Theatre Company artistic director Jasson Minadakis says he planned the company’s 50th anniversary season around its current production of “Native Son,” a bold new adaption on Richard Wright’s seminal 1940 novel by Chicago playwright Nambi E. Kelley.

It’s a devastating gut punch of a play. “Native Son” is the story of Bigger Thomas, a young African-American man furious at how limited his options in life are in white-dominated society. Shortly after getting a new job as a chauffeur for the rich white Dalton family, he helps staggering drunk daughter Mary Dalton to bed but accidentally kills her while trying to keep her quiet to avoid being caught in her room. Thus begins a feverish cover-up, as he knows no one’s going to listen to any extenuating circumstances.

This isn’t the first stage version of the novel. The author collaborated with Paul Green on a “Native Son” play that debuted as early as 1941, directed by Orson Welles. In 2006, Seattle’s Intiman Theatre premiered a new version by Kent Gash, who has also directed at MTC (“Seven Guitars,” “Choir Boy”). It’s also been made into a couple of movies, the first of which (in 1951) actually starred Wright.

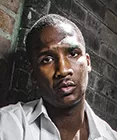

Director Seret Scott helmed the world premiere of Kelley’s version in Chicago in 2014, and she’s brought a lot of her team from that production with her to Marin, including costume designer Melissa Torchia, lighting designer Marc Stubblefield, sound designer Joshua Horvath, and actor Jerod Haynes in the lead role of Bigger Thomas.

Haynes is riveting as Bigger, tense and volatile, his simmering rage never far beneath the surface but deliberately suppressed around white folk. His discomfort when white liberals try to act chummy with him is excruciating, because he knows better than to try to respond in kind.

Rosie Hallett is cringeworthily condescending as Mary Dalton, a dilettante leftist who’s positively giddy to meet a real live black man. She and her boyfriend, a communist activist (absurdly earnest Adam Magill), are eager to show off how much they want to connect with “your people.” Mary’s blind mother (nervously chatty Courtney Walsh) also makes a big deal of how liberal-minded and charitable the family is. After all that, the straightforward racism of the private detective (a casually badgering Patrick Kelly Jones) is almost refreshing.

C. Kelly Wright is forceful as Bigger’s no-nonsense mother, and Dane Troy is an energetic presence as a confusing hybrid character combining his adoring little brother and a taunting friend. Ryan Nicole Austin fades into the background as Bigger’s little sister but commands the stage as the boozy girlfriend he doesn’t particularly like.

Scott’s staging is tense and dynamic throughout. Stubblefield’s stark lighting conspires with Giulio Cesare Perrone’s skeletal set of steps and platforms to lend a stripped down sense of urgency. Horvath’s suspenseful sound design mixes jazzy trumpet with dogs and sirens to suggest hot pursuit.

Kelley makes a number of striking changes beyond the usual paring down of plot and characters. She omits the last section of the novel entirely, which focuses on Bigger’s interactions with his lawyer. Starting with the death of Mary, the narrative skillfully jumps backward and forward in time, often shifting between Bigger’s interactions with his family and with the Daltons in the same scene.

Most crucially, Kelley creates the new character of the Black Rat (a coolly observing and advising William Hartfield), who acts as a kind of sinister Jiminy Cricket, providing the mocking commentary that Bigger can’t say aloud and prodding him to do whatever he needs to do to survive. But he isn’t just a devil on Bigger’s shoulder; he’s as likely to talk him out of doing something rash as he is to insist on violence when necessary. He’s not really outside of Bigger but part of him, embodying the cold, hard calculation necessary to navigate through a world that’s always, in one way or another, out to get him.

It’s a brilliant device that keeps us deep in Bigger’s head when we need to know not just what Bigger does but what drives him, because the society around him is all too ready to believe the worst about him. That’s just one of the reasons why it’s so sobering to revisit this story now, because that readiness to demonize doesn’t seem to have changed much.

★★★★★ 'Son' Rises Richard Wright's masterpiece hasn't lost its power

Beauty isn't always pretty.

Richard Wright's 1940 masterpiece Native Son—among the most important and powerful American novels ever published—has been alternately praised and condemned, drawing kudos and criticism for the very same things—mainly, the brutal honesty, realism and shocking violence of Wright's supremely crafted depiction of life as a poor, undereducated black man in mid-century America.

Powered by a poetic, elegant script by Nambi E. Kelley, the Marin Theatre Company brings Wright's explosive novel to the stage, with an extraordinary cast giving perfectly tuned performances under the steady guidance of director Seret Scott. The result is a remarkable theatrical experience that is at once astonishing, beautiful, visceral, vibrant and inescapably ugly. Kelley, succeeding where countless others have fallen short, strips Wright's epic-length novel to its bones, then dresses it back up again in brilliant theatrical ideas, enhancing rather than diminishing the power of Wright's ingeniously crafted, ethical puzzle-box of a story.

Bigger Thomas (a superb Jerod Haynes) is barely scraping by, living in a rat-infested Chicago slum with his mother (C. Kelly Wright), sister Vera (Ryan Nicole Austin) and brother Buddy (Dane Troy). Bigger is, for obvious reasons, a frustrated man, a combustible blend of anger, hopelessness and fear.

Bigger's violent internal struggles are brilliantly illustrated through his conversations with the Black Rat (William Hartfield), the playwright's impressively wrought illustration of Bigger's conflicted inner battles. The Rat represents the way society sees him, a view that is constantly in conflict with how Bigger sees himself.

Even the possibility of a decent job, chauffeuring for a wealthy, liberal white woman (Courtney Walsh), is rife with danger. Her daughter, Mary (Rosie Hallett), and her communist boyfriend, Jan (Adam Magill), attempt to show Bigger how open-minded they are, clueless about how their public shows of "equality" are putting him in danger.

As the story moves ahead with ferocious speed—told in a single, 90-minute act—Bigger steps back and forth from present to past, with flashbacks underscoring his rising fear and fury with heartbreaking power.

The story may be set in the 1940s, but that so little has changed is clear. That, along with the ugly beauty of his storytelling, is why Wright's brutal masterpiece continues to have such resonance after more than 75 years.

★★★★★

Collapsing a novel that is often listed in the top 100, most significant novels of the Twentieth Century not only into a play but also into a split-second-long setting within the main character’s racing, panicked mind is no small order and fraught with possible missteps. However, playwright Nambi E. Kelley has handed a tight, tense adaptation of Richard Wright’s 1940 novel, Native Son, to Director Seret Scott; and the result for Marin Theatre Company is a sweat-producing, heart-pounding production that starkly reminds us that the harsh, damning truths of 1940’s White America are in many ways not that different than those echoed by Black Lives Matter in 2017.

Ms. Kelley’s script incredibly captures in ninety minutes almost the entirety of the original, gripping novel that laid out in raw terms the racial divide of America that remained seventy-five years after the Civil War. A young African-American man, Bigger, living in rat-infested poverty in Chicago’s West Side of 1939, finds himself as the chauffeur for one of the city’s richest families -- the same Daltons who own the shabby, one-room apartment building where he lives with his mom Hannah, sister Vera, and brother Buddy. A first-night assignment to drive the rich family’s daughter Mary to university is hijacked by the socialite’s other plans to go out with her Commie-leaning, handsome boyfriend, Jan, for a night on the town.

They choose to hit the South Side’s black establishments, dragging uneasy Bigger into their night of boozing and carousing – all the time telling him “We are on your side.” But too much drink eventually leaves Mary both unable to walk and totally amorous toward the beautiful Black man who must now take the half-passed-out beauty back to her room in his arms. When the blind Mrs. Dalton comes in unexpectedly to check on her daughter just as Bigger decides to give in and kiss the pretty redhead, he panics and covers her head with a pillow to suppress any drunken sounds from her.

The rest of the story follows a too-familiar story that still plays out today for young, urban, African-American men. There is little chance for him to do anything but make all the wrong, ever-more-damning choices as the society around him comes to the all, too-quick conclusions based on its long-held, deeply believed stereotypes and prejudice.

The power of this re-telling of Native Son comes to bear in the split-second, fast-paced, tension-filled direction of Seret Scott. Interlocking scenes play out on a sparse, multi-level, wooden-famed labyrinth (designed by Giulio Cesare Perrone) where Bigger often physically moves between time periods of his life with spoken phrases from one incident being either finished or echoed in another scene and time period. Ms. Scott creates through astute, imaginative direction Bigger’s inner-brain, thought patterns that range from nostalgic memory to agitated anger to near-hysterical madness.

The large, figured shadows against black walls; blindly sharp spots at times centered on a lone Bigger; and a mixture of light and darkness playing throughout the maze of the set’s wooden slabs and steps are just some of Marc Stubblefield’s contributions to enhance Ms. Scott’s direction. Background, pinpointed effects of sound designed by Joshua Horvath set the tones needed to round out a picture the Director creates that portrays the contrasts of the slums and alley-crossed streets of the South Side with the homes of the upper crust of the same Chicago – the latter differences further enhanced through the costumes of poor and rich by Melissa Torchia.

The inevitability of doom for this man whom society has branded from the beginning as a loser is underscored by scores of decisions the director makes in taking the suggestions of the playwright’s inspired script and bringing them to life in ways that often appear as if a multi-screened movie is being shown before us. One of the most powerful images of the play and the novel occurs near the beginning when Bigger slaughters a foot-long rat before his first grateful and then horrified family. In Ms. Kelley’s version, the rat is played by a smartly dressed man in three-piece suit and hat, a presence who shadows Bigger throughout his dream/nightmare and who reminds him repeatedly, “When you look in the mirror, you only see that they tell you is a black rat son-of-a-bitch.”

As The Big Rat, William Hartfield exudes the ever-present premonition of the inevitable as he plays Bigger’s inner voice that eggs on, challenges, advises, and even tries to protect Bigger’s too-bound path toward self-destruction molded by the society around him. While he is on one hand through his growly, gravelly voice the personification of The Black Rat in the referred mirror, he is also dressed in business best and carries himself with the tall, proud stature of the Man that Bigger might have been if not pre-ordained otherwise.

As Bigger, Jerod Haynes never is out of our sight and from whom it is difficult to turn our attention even for a few seconds from his achingly powerful performance. While the character remembers in fever-pitched sequences all the event events leading up to his arrest and then projects in his dream the certain conclusion beyond, we see so many aspects of this complex character come to life in Mr. Haynes’ stellar performance. We watch him with amusement “Play White” with his brother where one is JP Morgan and the other is a poor, black worker. Or we watch as he looks to the sky mimicking planes flying high above, hearing his deep disappointment mixed with increasingly hate-filled resentment, “Man, I’d love to fly ... White folks don’t let us do nothin’.”

So tight and taunt Bigger is that, like a stretched rubber band, he often appears about to snap two. The sudden anger that does suddenly erupt -- especially to family members like when he requires his brother to lick a switchblade -- lets us know that here is a man who is gradually losing all control and judgment even as he fights always to look downward, answer ‘yes’m,’ and never contradict whenever the white folks around him. Mr. Haynes’s wide range of emotional constraints and outbursts, his wide-eyed moments of both anger and terror, and his animal-like moves and instincts hell-bent on survival balance against those moments when we see him just trying to be a man like other men, taking a few minutes to play pool, to joke with a pal, to love -- even to dream. Together, Messieurs Hartfield and Haynes portray a Bigger that must be causing Richard Wright to be smiling in awed satisfaction from somewhere in the Great Beyond.

And surrounding the two sides of Bigger in his dreamed sequences is a cast where each person leaves a merited mark on his and our memory. C. Kelly Wright is magnificent as the tortured mother who cannot understand why her son cannot just love Jesus, work hard, and be a good boy. As Hannah, she also rises in indignation when the White Man comes to seek his revenge on her just because he assumes she is guilty and worthless by association with her son.

Dane Troy is the kid brother Buddy, fully convincing in his wanting to be noticed and included by his older brother’s good and bad ideas but also heart-wrenching when he becomes the brunt of Bigger’s tirades. Doubling as Sister Vera and Girlfriend Bessie, Ryan Nicole Austin is appropriately sweet and silly, seductive and sultry.

Courtney Walsh is the blind Mrs. Dalton whose aristocratic dignity and societal status makes room for her somewhat feeble, but seemingly well-meaning attempts to show Bigger that she trusts him, no matter that he “a Negro.” Even more so, her flighty, laughing daughter, Mary -- with red-hair flinging in ways to taunt and tantalize (played by Rosie Hallett) -- and Mary’s left-leaning boyfriend, Jan (Adam Magill), together bend over backwards in almost cartoonish manners to ‘equalize’ Bigger to their white status. But as these mixed-up scenes play out in Bigger’s memory, it is clear that he begins to see the outreaches of Jan s having some deeper, truer sincerity, believably conveyed by Mr. Magill’s portrayal.

Rounding out the cast is Patrick Kelly Jones as the one-person representative of the white police force -- a detective named Britten who comes with all the power clearly on his side to push, provoke, and penalize Bigger and his family in any way he sees fit and just.

For more than three-quarters of a century, Native Son has jarred the thinking and awareness of both black and white America. As the stage adaptation arrives in a must-see production at Marin Theatre Company, the story of Bigger is shockingly still too familiar in a present-day America that has yet to figure out how to call a halt to the seemingly inevitable destruction of too many of her young, African-American men.

Rating: 5 E

“Riveting, dynamic, brilliant … a devastating gut punch of a play”

“Poetic, elegant, astonishing … a remarkable theatrical experience”

Native Son: Marin Theatre Company Takes on Richard Wright’s Classic Novel

It’s not surprising that Marin Theatre Company artistic director Jasson Minadakis has centered the company’s fiftieth anniversary season on Native Son, a new adaptation, by Nambi E. Kelley, of Richard Wright’s 1940 best-selling novel. In his eleven years with this excellent Bay Area company, Minadakis has made a particular effort to showcase plays with African American themes, by African American playwrights. And he’s brought us some terrific new work.

One of the first plays I saw at MTC, back in 2010, was Tarell Alvin McCraney‘s In the Red and Brown Water, the first in his Brother/Sister Plays trilogy (the other two were produced that season at theaters in San Francisco and Berkeley, respectively). Five years later, MTC presented McCraney’s terrific Choir Boy. Now he’s getting a ton of attention for Moonlight: A major Oscar contender, the movie is based on McCraney’s play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue; McCraney himself is up for an Oscar, with director Barry Jenkins, for best adapted screenplay.

In the past few years, MTC has also brought us Matthew Lopez’s The Whipping Man (the company’s third-best-selling production ever), Danai Gurira’s The Convert, and Will Power’s Fetch Clay, Make Man, not to mention three of the late famed African American playwright August Wilson‘s ten plays. All were superbly done and got rave reviews.

In my opinion, MTC is the most consistently excellent theater company in the Bay Area. Audiences have come to expect outstanding acting, directing, set and costume design, sound and lighting in any production we see here in Mill Valley.

Native Son director Seret Scott, who directed the play in its world premiere in Chicago, brought much of her team, including the leading man, with her. Jerod Haynes plays Bigger Thomas, who dreams of being a pilot but feels his every option limited by racism: “When you look in the mirror, you only see what they tell you you is.”

The story takes place during the Great Depression, when options for so many are few and even more curtailed for blacks. Tough to begin with, Bigger’s life derails when he’s hired by a liberal white family as their chauffeur. On his first night, he is to drive their rebellious, entitled daughter, Mary, to a university class; instead, she not only forces him to take her to meet Jan, her young Communist boyfriend, she makes Bigger sit between them in the car, drink with them, and show them someplace “you people” like to eat. The two even sing one of “his” people’s songs with egregious Southern accents. Their patronizing cluelessness—they have no interest in Bigger as an individual—is more painful to watch, and more interesting, than the flat-out racism he normally encounters.

When they get back, Mary is so drunk, he has to practically carry her to her room, where, trying to keep her quiet, he accidentally smothers her. Then he has to get rid of her body. Then he has to run. Then, led by his inner self and survival instinct, The Black Rat (“you only see what they tell you you is”), he kills again.

The novel makes every step Bigger takes inevitable, the product of society’s horrendous racism and his poverty. The play tries to take us inside Bigger’s mind by portraying “a split second...when he runs from his crime, remembers, imagines, [on] two cold and snowy winter days in December 1939 and beyond.” This imaginative conceit shuffles time, characters, and events, giving us tumbled shards of Bigger’s life rather than a straightforward rendering. This approach makes a plot that seems rather simplistic—certainly when compared to the plays mentioned above—appear more complex. And yet, with the murder taking place near the beginning of the play, the crime’s inevitability is muted. The action that follows is somewhat heavy-handed. And since we’ve already seen Bigger pull a knife on his little brother and lose control when bashing the rat that’s scaring his family, our empathy is muted as well.

Even so, the play is gripping, thanks to its intensity, pacing, and fine acting: William Hartfield as The Black Rat; Dane Troy as Bigger’s little brother and in some smaller roles; C. Kelly Wright as Bigger’s mother; Ryan Nicole Austin as Bigger’s alcoholic girlfriend (she also plays his sister); Rosie Hallett as Mary; and Courtney Walsh as her mother. Patrick Kelly Jones is properly despicable as various racist police and others, though Adam Magill, so memorable in Miss Bennet: Christmas at Pemberley, is given far less to do as the earnest Jan.

Native Son is a play worth seeing—and a novel well worth reading.